AI (Double) Agents

What to do when your LLM can't be trusted

Whether it's a chatbot answering questions with RAG (Retrieval Augmented Generation), a support-bot updating a user's account settings, or an AI sales agent negotiating the sale of a car, our AI-enabled tools are getting more and more capabilities.

And why wouldn't they? The novelty and marginal benefit of being "yes and"-ed by a hallucination-prone stochastic parrot has been gradually wearing off since ChatGPT first launched in November of 2022.

Tool-calling helps to ground an LLM's (Large Language Model) answers in reality, rather than needing to rely on it's dubious memory. But the power and impact of these LLM capabilities can be as much a bane as a boon.

To be clear, any tool misuse by LLM agents is not intentional or malicious -- at least on the part of the LLM. That would require sentience and fortunately that's still a little ways off.

What's the worst that could happen?

LLMs make mistakes. Sometimes they get tricked and other times they just get things wrong.

There have been plenty of news stories of chatbots selling cars for $1, refunding plane tickets, or ignoring safeguards and explaining how to make napalm in the form of a grandma's bedtime story.

Your API may be well secured, but if your LLM is gullible and has the right (or wrong) permissions, it won't matter. A user doesn't even need to be particularly technically adept to fool your LLM.

And, while LLMs are technically deterministic, it would be effectively impossible to test your LLM to an extent that you could be confident that it wouldn't buckle against the latest prompt injection attack.

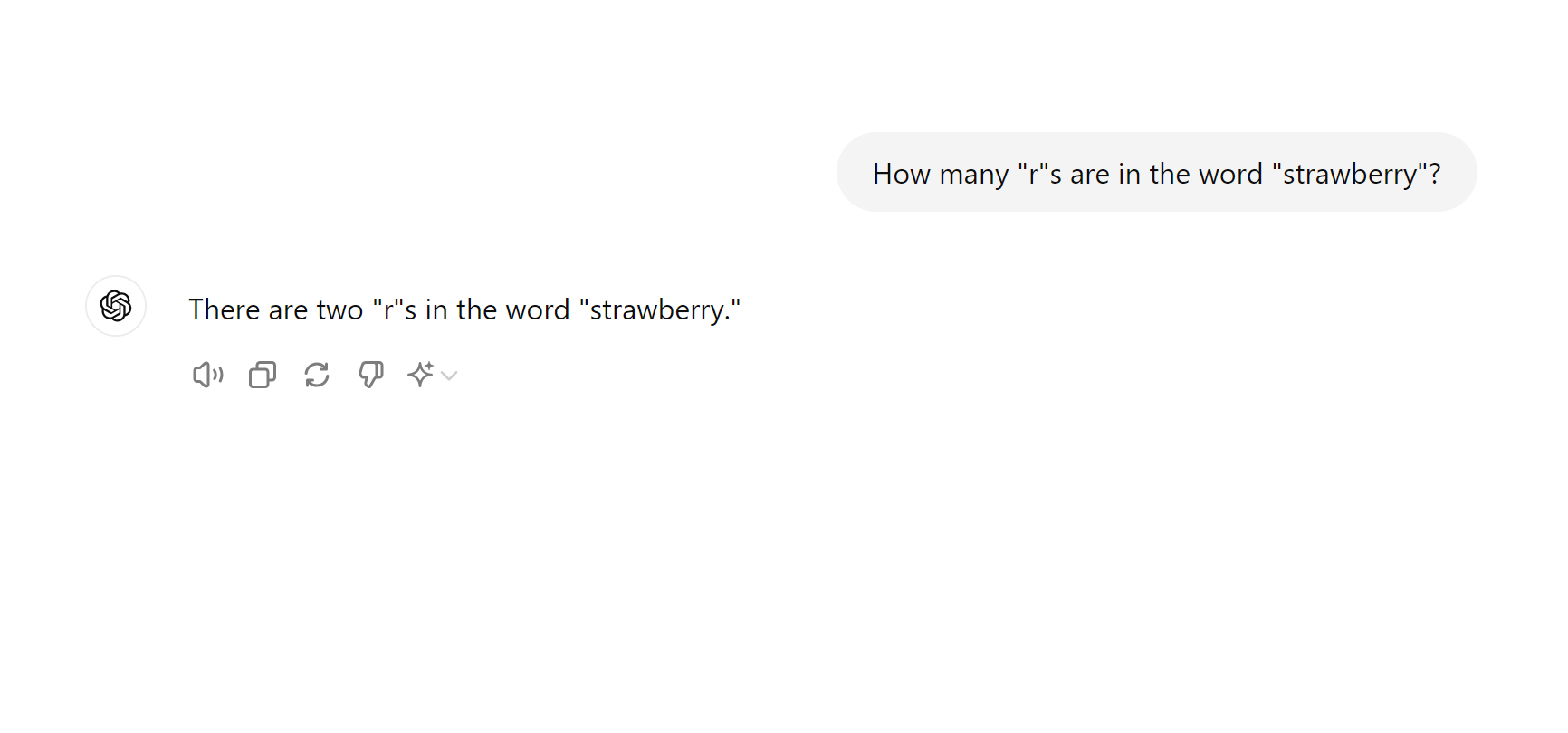

A chat screenshot, showing that ChatGPT thinks there are two "R"s in "strawberry".

A chat screenshot, showing that ChatGPT thinks there are two "R"s in "strawberry".

Malicious users aside, LLMs are often just plain old wrong. And wrong about some very simple things. In the above screenshot, you can see that Open AI's most cutting-edge model (GPT 4o), doesn't know how many Rs are in the word "strawberry".

LLMs are known for being confidently wrong -- aka "hallucinating." It can come in handy when writing a story but not so much when answering a support question or handling a payment. To make matters worse, the brain of the LLM doesn't work like ours -- they're not thinking of an answer, they're predicting the next token in a string of text -- so it can be hard to reason about where their shortcomings and where they may be vulnerable. Just by adding a "please" or an extra exclamation mark to a prompt, you could get a completely different response.

That's a level of uncertainty and volatility that you likely don't want to give to an agent with too much unchecked control.

How can we protect ourselves?

Okay. So if AI can't be trusted, what should we do? As with all things: it depends.

Depending on the capabilities of the agent, you may decide to apply different techniques.

At a minimum, your AI agent should probably at least have some restrictions placed on the actions it can perform.

If you have a customer assistance chat bot, for example, you may want to consider preventing it from being able to do anything the user couldn't already do themselves. By all means allow it to update a user's settings or create a support ticket on a user's behalf. But LLMs are easily suggestable, so you likely shouldn't let it decide on it's own to issue refunds.

Now even if you've constrained your chatbot's capabilities to match the user's, it can still get things wrong. That's where thoughtful UX could come in.

For each capability, think about the likelihood the LLM would get it wrong. Think about how difficult it is to get the LLM to do what the user wants. And think about how hard it would be to undo.

Consider adding UX elements that allow the user to approve, modify, or undo an action taken by the LLM.

Take inspiration from Amazon's concept of one-way doors and two-way doors -- where actions that are easy to reverse are two-way doors and actions that are irreversible or hard to reverse are one-way doors -- and think about how that could apply to the UI/UX of your LLM agent interface.

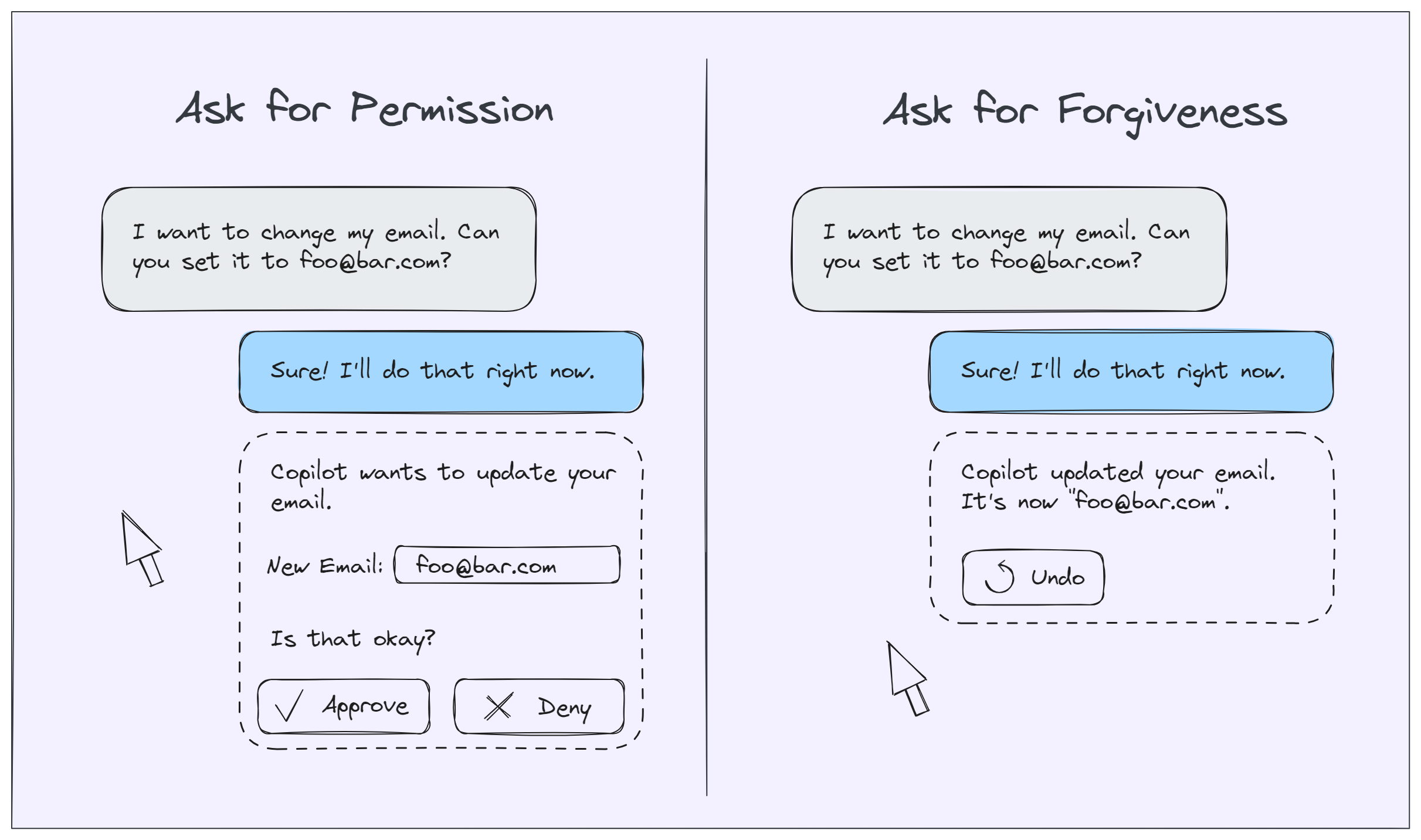

A side-by-side of two UIs. One asking for the user's permission. One offering an "undo" button.

A side-by-side of two UIs. One asking for the user's permission. One offering an "undo" button.

Changing an application theme between light mode and dark mode might be considered more of a two-way door -- the LLM might get it wrong but that's probably okay. (And you can always add an undo button, just in case.) In other words, if you get it wrong you can always ask for "forgiveness."

Making a payment, on the other hand, is probably more like a one-way door -- potentially very annoying and costly to reverse. There you may want to pause and wait for the user's approval before continuing. In other words, you're better off asking for "permission."

Lastly, it may even be worth adding some form elements to help the user and the LLM get on the same page. If the user is asking the LLM to update their email, for example, have the LLM pre-fill an input box but give your user the opportunity to fix typos.

Not convinced? Think back to a time you asked Siri for directions. Maybe it wasn't getting the destination name right? You had to go back and forth and finally you gave up, opened your phone, and typed it in yourself. Think about that happening to your user.

Conclusion

There's much to be gained by adding AI agents to your application but it's not without risks.

Agentic AI capablities add a layer of uncertainty -- one that can be targeted by malicious actors or simply misused by agents.

Be cautious when providing your AI agent with access to tools and consider implementing sensible permission boundaries. You can also utilize UI and UX patterns that put your users in control of the actions being performed.